Mzia Amaghlobeli is being detained since January. Her arrest is a warning shot against Georgia’s independent media. Her case reveals the erosion of press freedom under the foreign agents law—and a regime that fears truth more than dissent.

I first met Mzia Amaghlobeli when I was a teenager. We both lived in Batumi, where I’m from and where Mzia began her career in journalism before we met. When she was 26, she founded Batumelebi, a news outlet that aimed to prove that it was possible to practise real journalism and set standards in a region where the authoritarian ruler treated everything as his private kingdom. This was even true in a country emerging from the ruins of post-Soviet dramas and wars.

Over the years, this young reporter has managed to transform a small local newspaper into two prominent online media outlets in the South Caucasus region: Netgazeti, which covers national and international news and has won awards, and Batumelebi, which focuses on local news from Batumi.

Journalists bother people in power. When we choose a career in journalism, we know that we’re signing up for a challenging life. But there are things we don’t sign up for. Over the years, I have heard Mzia’s stories about how she and her journalists have been threatened, put under surveillance, followed and blackmailed. As a youngster, I would listen to these stories excitedly, as if I were watching a film. But what is happening right now is not exciting anymore. These are not things we signed up for.

Since the foreign agent law was first adopted last year, we have known that Georgia was going to go down the hill, and it was going to do so badly. At the end of the day, what we saw in the last seven months was not a backsliding, which people like to say: it’s like a landslide taking everything down with it as it falls from the top of the mountain.

Mzia’s controversial double arrestb

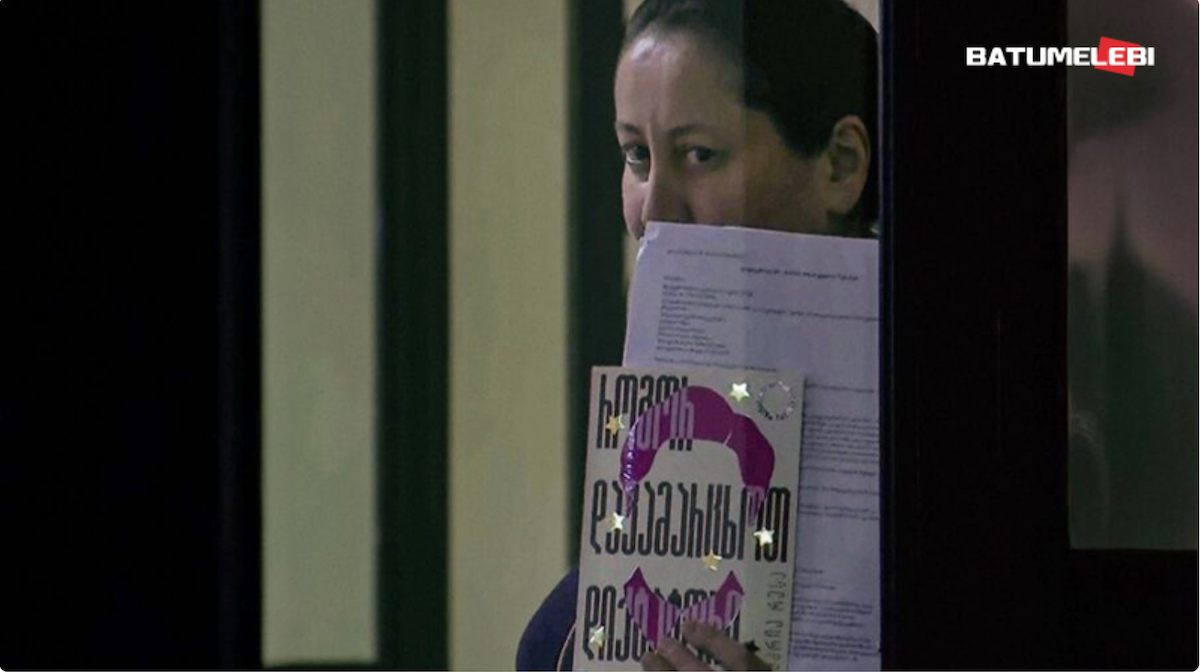

On the night of her arrest, between 11 and 12 January, Mzia was at the office in Batumi, the second-largest city in Georgia on the Black Sea coast. There was another protest going on, which was violently broken up by the police, with people being violently arrested. Mzia witnessed the arrest of one of her friends, activist and local civil society organisation employee Tsiala Katamidze, for placing a sticker saying “Georgia goes on strike” on the ground in front of the police station. She went to the police station, where some protesters were demanding the release of those who had been detained unlawfully. She also brought a lawyer with her to help her friend. After her arrival, the arbitrary arrests continued. Overall, nine people were arrested for either putting up a sticker or asking why people were being arrested.

In the video taken shortly after her arrival at the police station, Mzia is seen putting the same sticker on the external wall of the station’s checkpoint. The police then removed the sticker without leaving any trace of it, while several officers led by the director of the Adjara Police Department took her inside the building. During her trial, Mzia told the court that she had not intended to spread the message written on the sticker, but rather to protest in favour of freedom of expression and against injustice, and to show solidarity with those who had been detained unfairly.

Around an hour later, Mzia and the other female detainees were released from administrative detention. Like the others, she was charged with resisting, disobeying and insulting police officers, but none of these charges are confirmed by video footage or independent witnesses. After her release, Tsiala Katamidze told journalists that, while in detention, she had heard the voices of male detainees being beaten. She named the men, who confirmed it.

Now that the female detainees had been released, the rally was beginning to disperse. However, a small group of former detainees, including Mzia, as well as some friends and relatives who had come to the station after hearing of the arrests, remained on the spot to discuss what had happened. At this point, a group of police officers stormed out of the station yard, approached the group, and arrested one of them. This caused some confusion amongst the protesters, which eventually escalated into a clash with the police. In the video, Mzia can clearly be seen caught in the middle of the crowd, being pushed to the ground and disappearing.

The police detained two brothers related to Mzia, then retreated behind the station yard’s gate. In the video, Mzia can be seen near the gate, struggling with one bare foot. She and others were trying to find out why the latest arrests had been made. Eter Turadze, a close friend of Mzia’s and co-founder of Batumelebi, later recalled that they were afraid the boys would be beaten at the police station simply for having stood with them.

Mzia can then be seen asking Batumi Police Chief Irakli Dgebuadze why her relatives had been arrested. He responded that they had sworn at the police and turned his back on her. Mzia can be heard telling him: “Just like when your policemen arrested me…” At the same time, she pulls Dgebuadze’s sleeve to get his attention, but before she can finish her sentence, she slaps him.

Mzia was then arrested for the second time by several police officers and taken to the police station. In the video, Dgebuadze can be heard swearing and threatening her with criminal charges.

More : Why Europe must support independent journalism in (and about) Ukraine, Belarus and Russia

We later learned that, while in detention, Mzia was kept with her hands cuffed behind her back for several hours, and was denied access to drinking water, a toilet and a lawyer. Dgebuadze repeatedly threatened her with physical violence and tried to storm into the detention room, eventually spitting in her face. None of this has been investigated.

Over three hours after her arrest, we learned that she had been charged under Article 353-1 of the Criminal Code for attacking a police officer, an offence which carries a potential prison sentence of four to seven years.

At the preliminary hearing on 14 January, the judge at the Batumi Court sided with the prosecutors and claimed that Mzia’s prior administrative arrest was sufficient grounds to believe there was a high risk of reoffending. The judge denied her bail in any form and sentenced her to pre-trial detention. She has been jailed near Tbilisi since then.

Some important facts: “Attack” under the Georgian Criminal Code has specific qualifying criteria, and slapping someone in the face never qualifies as such.

The administrative arrest was illegal. Her first arrest was witnessed by many people, and it is clear that she was not resisting, disobeying or insulting the police. However, the police tried to justify the fabricated charge by submitting video evidence to prove that Mzia was “resisting the police”, thereby justifying the administrative arrest. The problem is: This video was recorded after she had already been released from administrative detention, so it cannot show the offence she was originally accused of.

In fact, the video shows Mzia being physically assaulted while surrounded by clashing police and citizens. She is a victim, not a perpetrator.

I am going into such detail so that people can understand just how badly forged the case against her is: even the evidence has been manipulated. Mzia was also charged with distorting the appearance of a building for putting a sticker on the police station for about ten seconds. The most ridiculous part of her case is that the police wrote in the report that Mzia had received instructions to slap a police officer during a phone call. Based on this report, the court issued an order to access her phone and all the data it contained. They wanted to make her appear to be a foreign agent.

Mzia was targeted by the regime partly because Georgia has a vibrant and diverse media landscape with critical and independent voices. Smear campaigns accusing independent media outlets of representing the opposition or business groups don’t work because the media outlets have very close ties with communities and people know the journalists. Therefore, it’s very difficult to attack the reputation of independent media in a country of this size [Georgia has 3.7 million inhabitants]. This is why Mzia is being made an example of: it’s not only her who is on trial, but independent media too. Georgian journalists understand this perfectly.

Despite their individual differences, they are closely following this case because they believe they are in this together. This is evident in the details, such as sharing material, offering footage for free, live streaming and planning a joint talk show. A documentary film about Mzia’s case was streamed simultaneously on most of Georgia’s independent and critical media outlets.`

Maria Ressa’s example and the importance of international attention

In mid-June, at the ZEG festival in Tbilisi, I had the opportunity to speak on stage about Mzia’s case and discuss it with Maria Ressa, the CEO of the Filipino Nobel Peace Prize-winning investigative media outlet Rappler, who joined us remotely. Maria had also been harassed by the previous administration in her country, and we realised how similar our experiences were. I wish there was more awareness at a global level, particularly within the global journalism community.

A few weeks ago, I was interviewed by a Hungarian journalist who wanted to talk about the impact of the foreign agents law because, she said, the same kind of measure is expected to be enforced in her country too. Hearing this was painful for me because just a year ago, I was interviewing Russian and Belarusian journalists, trying to use their experience as a wake-up call. I thought about this Hungarian journalist and wondered if they would be interviewed by Slovakian journalists next time.

I believe there are people around the world who look at Georgia and think, “We’ve seen this before. It’s going to happen, and there’s nothing we can do about it”. I want to make it very clear that it’s all up to us. We can reverse this trend and set an example that it can be reversed. Maria Ressa showed us how to fight and ultimately be free.

In her speech at ZEG, human rights barrister Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC made three interesting points. The first is that international solidarity provides resolve and psychological support. But it also has a real impact on the legal strategy because cases like Mzia’s are political cases, not legal ones. “Knowing that the world is watching and that support is out there undoubtedly impacts decision-makers. We saw that in Maria Ressa’s case”, she said.

“At one stage, Maria was described by someone from the authorities as a prostitute. When you look at Georgia’s foreign agent law, you’ll see that it’s very similar,” Gallagher said. “The language used refers to pursuing the interests of a foreign power. It is designed to undermine the nature of journalism and journalists; to suggest that they are just selling their wares and peddling a line they don’t believe in. I know that, for Mzia, journalism is not only a profession, but also a tool for social change. One of the things I admire greatly about her work is her efforts to document Soviet-era repression and seize back the narrative through her work on historic memory.”

As Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC pointed out, the authorities “have been waiting a long time to silence Mzia, and they needed a good excuse”. Several journalists had already been physically assaulted by the time she was arrested, but what happened to Mzia goes further than attacks on individual journalists because “she is an emblematic figure. Her arrest was designed to send a very clear and chilling message to the media ecosystem across Georgia.”

The problem is that “we are not dealing here with a system that complies with the rule of law”, Gallagher said. A whole host of forcible actions have already taken place in this case: the criminal investigation was led by the officer who was the alleged victim. “It is clear that in Georgia, you are not going to get a fair trial,” she added.

“Mzia hasn’t had due process yet. What will make the difference here is ensuring that the world is watching and that there’s a proper international strategy,” Gallagher said: “The attempt that has been made in Georgia with the foreign agents law is to shut the world’s eyes. It’s a classic tactic: you run a smear campaign, undermining journalists and journalism for years; you try to cut off their lifeline within the country; you try to criminalise funding from outside the country; and you try to ensure that those who stand up for individuals – even lawyers within the country – may also be targeted under the foreign agents law if they receive international support.” It’s a perfect storm in which the person at the heart of it, the person in prison, is at the mercy of an unfair system and not receiving the necessary international support.

Now, more than ever, it is crucial that the case receives proper international attention.

I believe that we have no choice but to fight: we have a country to take back because, although the institutions have been captured, not all minds have

One of the difficulties we face is that “many of the countries with the most leverage over Georgia are not friendly towards journalists. You’re dealing with China and Russia, for example. However, I believe the key here is going to be the actions of the Council of Europe, the European Union and Germany, as Germany is one of Georgia’s main trade partners”, Gallagher explained.

Personally, I believe that we have no choice but to fight: we have a country to take back because, although the institutions have been captured, not all minds have been. Unlike in several other countries, things happened so quickly in Georgia that propaganda didn’t have enough time to capture the minds of citizens and the public. Propaganda needs time to achieve that, so we still have a chance because we have fighters. All the journalists who were hospitalised, fined or placed in administrative detention returned to the field and continued working.

More : Angry and betrayed, the Georgian people take to the streets to reclaim their European destiny

But we’re running out of time: Mzia’s condition is not good. After our cameraman was arrested, she went on hunger strike for 38 days, which took a terrible toll on her health. On 12 May, Mzia’s 50th birthday, people gathered outside her prison, sang songs and lit candles. She is weak and is still losing weight. Her eyesight has deteriorated drastically since the hunger strike and she can barely read.

The last time she came to the courtroom, she looked like a walking skeleton – I was terrified. Mzia stood in the dock for five hours without sitting down, to show her strength and determination to fight. She had travelled six hours by car to get there – she is detained near Tbilisi, but hearings take place in Batumi. This show of strength inspires us to continue the fight.

This is a difficult task, made harder by the pressure we’re facing from multiple directions at Batumelebi/Netgazeti, while at the same time our resources are rapidly depleting. We have therefore launched a donation campaign to raise emergency funds. It’s not the amount that matters, but the number of supporters – even a small contribution would show your solidarity and give Mzia and us all renewed strength. We would be grateful to have you with us.

| The Georgian media crisis: challenges and expectations |

| In the last two years the ruling Georgian Dream enacted sweeping laws to suppress independent media. The “Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence” labels media and NGOs receiving foreign funds as “foreign agents,” risking criminal penalties under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) for non-compliance. Amendments to the broadcasting law empower the national regulator to censor content and revoke licenses, while a new grant law places donor funding under state control. These measures aim to financially, legally, and reputationally cripple independent journalism, eroding press freedom and public accountability. Over the past years, Georgia has witnessed an alarming increase in uninvestigated cases of violence, threats, and harassment targeting journalists. According to data compiled by the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics and the Media Advocacy Coalition, dozens of reporters have been physically assaulted while covering protests or political events. The European Union has long supported Georgian media outlets by providing funding and institutional backing, which has enabled them to uphold journalistic standards. However, the scale of the recent crackdown, as evidenced by Georgia’s fall to 114th place in the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, requires further action. While financial aid is still important, the absence of decisive action leaves journalists vulnerable. Coordinated smear campaigns, threats and attacks, which often go uninvestigated, highlight the need for the EU to increase its engagement in order to match the severity of the crisis. Amid this crackdown, Georgian journalists are looking to the EU for strong support. The media is calling for a tougher stance from the EU to counter Georgia’s authoritarian slide and ensure that its commitment to democracy is not undermined by geopolitical hesitancy. The EU’s response to Georgia’s increasingly authoritarian trajectory has been characterised by a combination of hesitancy, diplomatic caution and missed opportunities. This has emboldened the government, which interprets mild statements and slow procedural responses as green lights rather than red flags. Mzia Amaghlobeli’s arrest has galvanised media communities worldwide, with her case coming to symbolise the broader fight for press freedom. Although some journalists feel isolated due to local repression, international solidarity in the form of joint statements and cross-border collaborations sustains hope. This unity strengthens their determination, demonstrating that Georgian journalists are not alone. Mzia’s case is testing both Georgia’s democratic future and the EU’s commitment to its principles. Whether independent journalism survives or succumbs to authoritarianism will depend on decisive action from Europe. Based on what has been said, Georgian independent media envisage the following actions as part of effective measures: – Publicly and continuously denounce the criminalisation of the media through FARA-style legislation. – Support strategic litigation at the national and international levels, particularly through the European Court of Human Rights, to challenge the compatibility of these laws with human rights norms. – Provide emergency legal and financial aid for media outlets under legal attack. – Build legal defence coalitions and refuse to let isolated outlets stand alone. – Public campaigns by European media networks to highlight cases such as that of Mzia Amaghlobeli could put pressure on the Georgian Dream. Ultimately, what is happening in Georgia is not an isolated case; it is a test for the region. The methods being used against independent media — stigmatisation, economic suffocation and criminalisation — are easily exportable and can be replicated wherever resistance is weakening and propaganda is gaining ground. |